This is a short extract from my book UGLY: Why The World Became Beauty Obsessed And How To Break Free which is available for pre-order here from today. It will be published on May 9th 2024 in the UK and commonwealth, and in the US in 9th April 2024.

Such is the nature of the human brain, as we go through life we collect bias from all sorts of places, mostly without realising and often while telling ourselves that we are being totally open and fair-minded.

We absorb it from pop culture, the media, the views of our caretakers growing up, our peers and, increasingly, our tech. Science suggests that we are automatically biased towards our own ethnicities; studies have shown that infants of six to nine months show preference for their own ethnicity and bias against those who are different. The ‘other-race effect’ offers that we are poor at distinguishing individuals from other races — hence that rhetoric often used for minority groups ‘all looking the same’. Bias towards our own race could even come down to our pack mentality, a legacy of cave-dwelling days — those who are in the pack are safe, those who seem different, other for whatever reason, could be a source of danger.

Unconscious (or implicit) bias refers to unconscious beliefs and assumptions that we don’t recognise we have. This often comes into play when we have to make quick judgements and assessments. Whereas conscious bias is, obviously, when you are aware of your preference for or aversion to something, extreme conscious bias may manifest as physical or verbal harassment or exclusionary behaviour.

Conscious racial bias is generally easy to spot and call out. Like somebody on a dating app saying ‘I only date white women’ (which I saw just recently). But unconscious bias, by its nature, is harder to unpick. It comes in the form of not questioning why we hold certain beliefs, or not even recognising them as beliefs, rather ‘facts’. For example, in the early days of my magazine career, people would openly say that make-up ‘didn’t shoot as well on dark skin tones’ as the acceptable reason for excluding models of colour from beauty editorials.

This kind of bias is one more way of excluding non-white beauty from the mainstream, another excuse not to address lack of representation, sure. But — and bear with me here — there could be some truth in it, stemming from limitations within photographic technology itself. The medium itself was created by and for white people, and when photographic technology was commercialised, it catered to the more affluent and dominant white market.

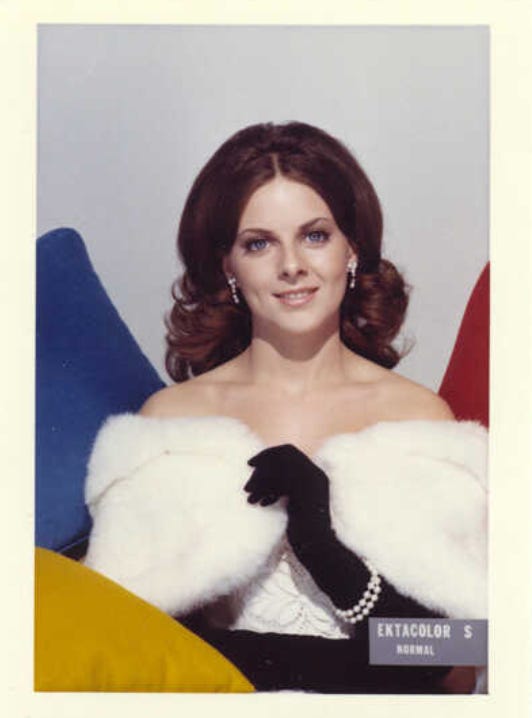

As colour film became more widespread in the 1950s, Kodak, which, at the time pretty much held a monopoly in the US, introduced something called a Shirley card. Your film was sent to a lab to be developed and a photo of a white woman with brown hair called Shirley — marked ‘normal’ — was used as the control for how colours should be adjusted. Eventually, more Shirleys were added to the fold - all white of course. But it took complaints from furniture and chocolate manufacturers in the 1970s, who were frustrated that you couldn’t see their shades of brown properly in their adverts to force their hand to address the colour bias in the technology. Rather than, you know, considering people of colour.

Kodak and the other photographic companies did eventually try to redress this with ‘multiracial’ Shirley cards and Black, white and Asian Shirleys, though not everyone used them. As digital photography ended the need for lab-developed photography and Shirley cards in turn, some of this bias towards how people of colour appear in photography was carried over into digital technology. Nigel Atherton, photographer of over 30 years and editor of Amateur Photographer, told Wired: ‘Exposure systems on cameras have always been weighted towards providing a pleasing exposure with lighter skin tones. Modern digital cameras and phones using AI are more sophisticated, but I find they still can’t entirely be trusted when photographing darker-skinned subjects.’

If you have dark skin and ever wondered why your face disappears into any background darkness, this might be why. And why magazine shoots of celebrities of colour are lightened or edited — though, often, far too much. What started as conscious bias — a belief that it wasn’t important to cater to all ethnicities in photography — evolved to become a form of technology bias and literal ‘white gaze’ that we cannot even detect.

These examples illustrate something that is so important because it affects so many areas of everyone’s lives and yet we hardly think about it, if at all. Our lives are now dictated by a small block of metal and plastic that is pretty much always in our hand or at least within reach. We might think that we are in control of the content we chose to look at on our smartphones but the reality is that so much of what we read, watch and see is curated by somebody — or something — else. Often we are tracked in order to serve us what our phones think we want to see from what we’ve been speaking about, watching and searching for.

This wouldn’t be so bad if the technology was a benevolent, fair dictator, free from the biases of the human society that created it — but, of course, it’s not. And, because it’s futuristic and forward- thinking, we so seldom stop to question its motives….

To read more more please pre-order UGLY in paperback here:

Being a woman of colour in the publishing industry has been eye opening! I’d love your support in helping me get UGLY out to as many people as possible by pre-ordering it above.

Big love and HUGE thanks for your support.

As someone who works in tech and is also a part-time photographer, I’ve never really thought deeply into how technology has affected the lives of people of color. We almost always just see technological advances for their benefits and rarely for their misgivings. I’m excited to get to read your book!

So introspective. Thank you for this. Just another reminder of the many things are rooted in racism and classism, even things you could never imagine.