Can you be brown and a goth?

There's a lot more kinship between being Indian and being a goth than I'd ever realised...

Last week, I went to two Diwali parties back-to-back. That’s impressive because I’m now 41, but also impressive because I tried a new look. I threw on a black sari, lubed myself into a latex corset and fake bleached my brows for a look that was part brown goth, part 90’s Vivienne Westwood fever dream. My jewellery was a mix of Camden market’s best and Amrapali’s finest molten silver with chunky gems and maximalism as sacredness. I carried a patent black and silver Dior bag that matched my bindi - until I sweated it off in between events clambering into the back of a black cab (that part was far less chic, tbh, forget I mentioned it.)

It sounds like something I moodboarded for weeks, but it was really just a panic pivot born of having a stack of Diwali invites (a joy) and a lack of budget for glamorous designer outfits (abject fear). But somewhere between pleating the sari and buffing latex gloss onto the corset, between tradition and defiance, I realised I’d accidentally merged two sides of myself that had always sat uneasily together: my Indian heritage and my lifelong gothic sensibility. That’s no small thing - I picked goth over being Indian for so long that feeling connected to my heritage again, alongside the alt culture I love feels quietly radical.

Diwali and goth culture share a strange, poetic kinship. One celebrates light; the other worships shadow. Both are, at their core, rituals about power; about what happens when darkness is acknowledged rather than feared.

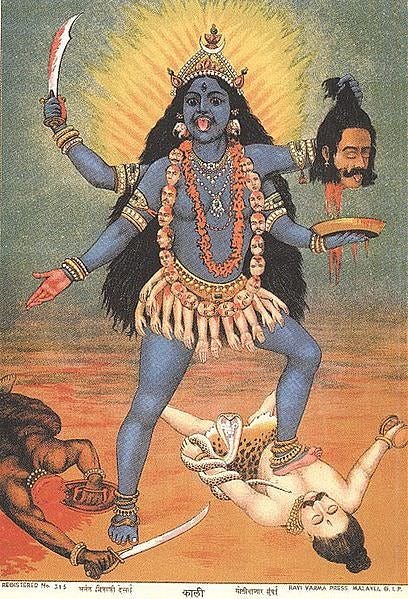

In Hindu mythology, light doesn’t erase darkness; it transforms it. The goddess Kali, for instance, isn’t evil as such - she’s destruction as creation, chaos as a catalyst. That’s peak goth energy if I’ve ever seen it. The Hindu fascination with death, decay, and rebirth - the very thing Victorians fetishised through their mourning couture - has long existed in South Asian spiritual tradition. We were doing existential macabre centuries before the West put it in a corset.

So when I wore that latex corset as a sari blouse, it wasn’t ironic or an attention-grabbing stunt, it was more a personal reclamation. A small act of owning the power and duality I’ve spent years trying to reconcile: the light and the dark, the sacred and the subversive, the parts of myself that were never meant to coexist, but finally do.

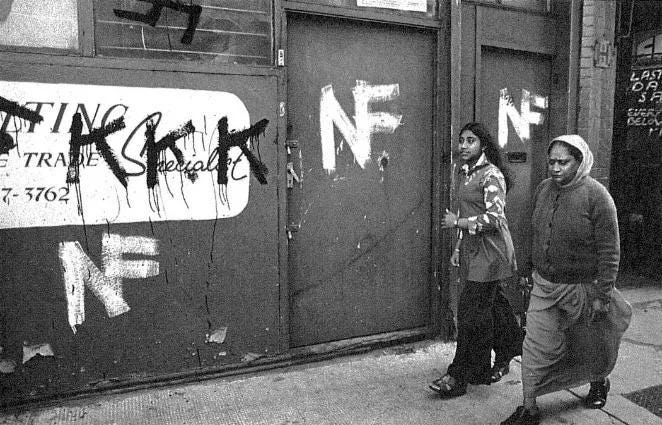

I spent most of my teens - and a good portion of my adult life - rejecting my Indian heritage in every way I could. Growing up in South Wales in the 90s, in a mostly white community, fitting in wasn’t just about wanting to look like the girls in Just 17 or Mizz magazines; it was about survival.

Fear created by The National Front still lingered in the cultural backdrop, and “Paki” was the slur that echoed across playgrounds and high streets alike. In small-town Wales, being visibly brown felt like walking around with a target on your back. So I made a choice, as so many of us did back then - to be as British as possible. But that came with its own kind of loss. In rejecting my heritage, I’d also rejected a part of myself. What replaced it wasn’t belonging, but a kind of restless, beautiful anger - the kind that eventually found its outlet in heavy alternative music, and eventually I developed a more gothic sense of style.

I didn’t have the language for what I was doing, veering towards black felt instinctual. All I knew was that black eyeliner, crushed velvet, and listening to Clan of Xymox made more sense to me than bronzer and The Spice Girls (although, I did also love them too.)

But looking back on that period, I realise that I was also rejecting the pressure to be perfect; both in an Indian and a western sense. Goth was my first act of rebellion against the western beauty standards and Indian cultural conditioning I’d already swallowed enough of. I knew I’d never fit the profile of what a “good Indian girl” was meant to be like: lighter-skinned, slim, well-behaved, elegant, Bollywood-adjacent (see above). So why even bother when the benchmark was so out of reach?

By western beauty standards “pretty” meant one thing only: thin, straight-haired, and white, as well as being girlish, sweet, agreeable - the kind of docility that gets mistaken for desirability. Those were boxes I’d never managed to tick either - so few ever could, no matter your race.

At times wearing traditional South Asian attire has felt a bit like I was in a costume. Because I’d opted out of the culture for so long, I knew so little about what was cool or in style. So at my first Diwali party a few years ago, I panic shopped in London’s Green street and turned up in something I probably would’ve worn at 18 - completely unaware that South Asian fashion had evolved while I was busy avoiding it. That’s what makes this new phase of my style - the merging of goth with South Asian - feel like closure and integration and it’s genuinely exciting to carve a new path here.

Many of the big South Asian designers already flirt with the gothic, whether they mean to or not. Rahul Mishra’s pieces (above) have a kind of Maleficent grandeur - sculpted shapes and shadowy embellishments feel straight out of a fairytale gone deliciously wrong. And Sabyasachi’s black-and-white heritage collections? They’re like the soft-focus cousin of goth - ornate, melancholic, and endlessly romantic. Exactly my kind of mood: sari-clad sorrow with couture-level precision. It’s a reminder that “fusion” doesn’t have to mean dilution. There’s something deeply empowering about using adornment not to prettify, but to signify lineage and rebellion in the same breath.

I’ve realised that getting dressed for Diwali isn’t just about celebration anymore. It’s about ownership. For years, I approached it half-heartedly - haunted by that teenage instinct to downplay my Indian-ness, and then not feeling like I was Indian enough to know what was cool, and wear it with confidence. But now, I want to play with it, exaggerate it, make it cinematic. And I’ve managed to find allies who subscribe to the same ethos; of doing Indian their own way - something that’s only spurring me on to experiment in the area between both worlds.

When I showed up at the Creed party in black latex and a sari, people smiled, complimented, took pictures and videos (like the one above with my friend Vithya.) But more than that, they understood. It was a look that said: I can honour tradition while rewriting it. The more I think about it “aesthetic refusal” is the ultimate stand off in a world that still prizes smoothness, gloss, and glow. To be a goth amidst our current conservative beauty standards is still bold and is still some 30 years later, a visual protest against the pressure to be palatable and mainstream. When you’re a brown woman raised under the double weight of Western beauty ideals and your own cultural respectability, that act of defiance means so much more.

And maybe that’s why goth never really really leaves you. You rarely hear of people suddenly embracing fluffy pink and rejecting their previously haunting ways. You seldom ‘grow out’ of being a goth. You might stop wearing the uniform, or adapt it to your own style, but the instinct - to challenge, to expose, to question beauty’s moral codes - ultimately always remains.

That’s exactly what I felt this Diwali. Between the marigolds and martinis, the latex and laddu, I wasn’t trying to fit in on either side anymore. I was finally expressing beauty on my own terms and it looked like both rebellion and confidence; one part Kali, one part Morticia. No longer begging for acceptance; just existing - uniquely and defiantly.

Much love, Happy Diwali and Bandi Chhor Divas…

PS: My full Goth Beauty Edit drops next week the best black liners that don’t smudge, the only metallics that show up properly, and the products that make rebellion a fine art….(if it’s not your vibe, then tell a gothic pal!)

As a fellow brown goth/alternative girlie I love this!

Brilliant article Anita, its so lush seeing you step into your power like this, diwali hapus iawn i ti ❤️🪔