Is 'minimalist beauty' a trend, or a warning that conservative beauty standards are back?

From 'clean girl' aesthetics to undetectable tweaks, today’s beauty ideals promise natural perfection - but do they mask a return to conservative beauty values?

Thanks for reading The Powder Room; a safe and explorative space to discuss beauty culture and identity, and to cut through the noise with expert recommendations. I’m a beauty editor with over 15 years experience, so do consider upgrading to a paid subscription with extra content and access; it really means a lot.

The current beauty standard doesn’t really feel like a hard work, does it?

It actually looks pretty effortless: neutral nails, dewy skin, sleek buns, glossy lip balm. But scroll after scroll, something starts to feel familiar - eerily so. It’s not just the “clean-girl” look, or the way that fashion has become more uniform and less individual - it’s the entire vibe that just a little feels off.

You don’t notice it at first, it just seems like a trend; like contouring or that thing where people put highlighter on the end of their noses like a frostbitten Rudolph. But before long, it starts to seep into your veins; instead of the blue shadow you reach for a neutral shade. When doing your hair, you opt to slick it back with a centre parting or claw clip. I know, because despite being a fan of bold beauty looks, this actually happened to me.

I’d seen so much of the same uniform look that I’d unknowingly started to adopt this more conservative look; and that’s no algorithm based accident; we’re seeing this shift unfold in real time. On TikTok, on red carpets, and in ad campaigns, the beauty ideal is changing. Gone is self expression; trending hair colours have transitioned from playful shades to more acceptable shades of blonde and bronde (that’s blonde and brown mixed btw). Blowdries have become big and bouncy again, and manicures have morphed from brightly coloured hues to pale pink shades with a hint of nail art for those with a hint of subversion.

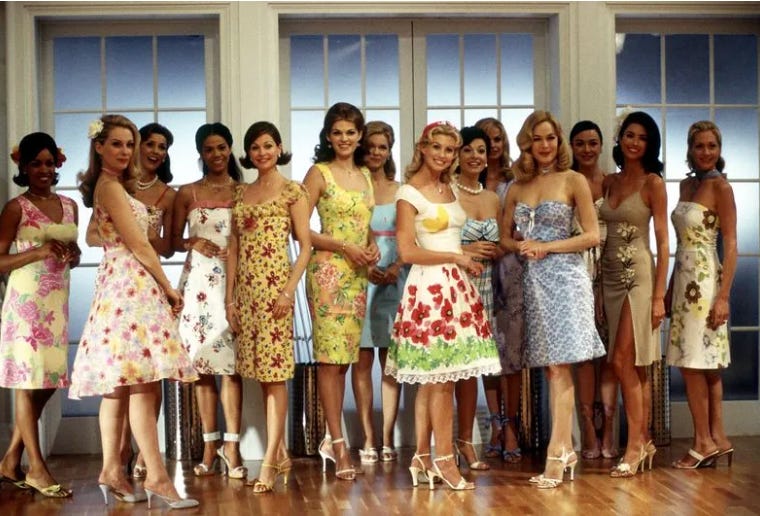

In their place is a new version of soft-focus femininity, poreless skin, slim bodies and youthful faces that might have been tweaked, though we can’t see it. We’re living through a reinvention of “traditional” beauty - only this time, framed as “good genes” and looking natural. And those we see on our social media feeds and on our screens are of course, almost entirely slim, white, young women. The kind that The Cut snapped (above) at a recent conservative conference that was held in the US for young women.

Across the West, there’s a tangible cultural contraction. In the US, reproductive rights are being rolled back and anti-trans legislation is surging. In the UK, race relations are at a low, trans rights are under threat, and a soft nationalism is seeping into everyday life. Whilst fashion trends often predict a forthcoming political retrenchment - for seasons the high street shops have been filled with muted tones and conservative silhouettes - now beauty has become the new barometer for predicting political and social change. With any hard fought gains for body positivity, inclusivity and self expression over the last few decades backsliding, it echoes how very divided our societies feel. And when beauty - of the most accessible forms of self expression - goes quiet, after being so loud, we should always ask why.

Haven’t we seen this before?

Periods of political conservatism have long influenced how women are perceived, often narrowing acceptable beauty ideals in the process. In 1950s America - an era marked by domestic containment and racial segregation - beauty standards exalted the white nuclear housewife: clean skin, curled hair, neutral-ish lipstick, and demure fashion that signalled her political and ideological alliances.

You can see how this happened; those in power were so fearful of the idea of integration (and women wanting to work post-war) that it doubled down on elevating Eurocentric beauty standards. Similarly, during the height of colonisation, American, French and British writers started to describe people from Africa or Asia as gluttonous savages with little to no self control or moral compass. Why? As misplaced dislike of their own growing waistlines (a result of the spoils of colonisation and international trade) and as a way to distinguish the superiority of Eurocentric beauty. And mark it as the ideal everyone should aspire to.

We live in vastly different times, but there are interesting parallels. With the MeToo movement holding powerful men to account for their actions towards women, and Black Lives Matter holding those in power to account for their numerous systemic misdeeds, both white supremacy and patriarchy have had their power and dominance threatened, like it was in the 1950s. As a result it’s given rise to anti-women communities, and swathes of anti-POC sentiment, and of course, our current beauty standard. It might not looks as kitschy, but it’s certainly uniform, and certain elevates the same things namely whiteness, minimal make-up, youth, slimness and often blonde hair.

To me, it feels like the 2020s are exacting the same sort of conformity we’ve seen in history; but it’s being repacked and resold to us as a new must-follow minimalist beauty trend. From using beef tallow on the face which was amplified by tradwife* influencers like Nara Smith, through to the trend for barely-there fragrances that smell milk or skin. I don’t know about you, but as somebody who lived through the 90s and 00s with their rigid beauty standards and conformity, it all feels stifling, or worse; suffocating.

Conservative beauty standards may be filtered through AI and Instagram - both riddled with the biases of their largely white largely male creators (read more about that here) but the function is the same: uphold the status quo and elevate the elite at the expense of those who deviate.

From maximalism to minimalism - again…

We’ve seen this pendulum swing before. The 2010s were defined by maximal (see above) beauty looks; contouring, overlined lips, technicolour palettes, festival glitter, and Instaglam everything. It was drag-adjacent, disruptive - often Black and queer-coded, and highly influenced by subcultures. This was the era of Obama, Me Too, and BLM, and for many people, the hope of a future with more fairness.

But since then, the rise of minimalist beauty has become a palpable symbol of conservative beauty; led by brands whose hero offering is barely there, no make-up make-up, a whisper of colour, a deeply average tinted lip balm. This could be framed as a backlash to the loud looks the decade before, but it’s also a symptom of power snapping back into the hands of those it was briefly wrested from. The beauty brands that work with the “trad wife” contingent like Ballerina Farm, and Nara Smith show how well far-right propaganda has infiltrated the mainstream - and perhaps hints at the ideals those brands might hold themselves. (There is one Trump-supporting brand founder who I’ve heard actively prefers the glossy blonde beauty editors in our industry.)

That E.L.F beauty paid 1 billion dollars for Rhode - a nice but fairly middle of the road brand popularised by a tinted lip balm and Hayley Bieber - it was a real sign that this ( despite any political affiliations Bieber and Rhode may have…I genuinely don’t know) is the shape of beauty to come. In our beauty aisles, social media screens, ad campaigns and what we’ll continue to be sold as the ideal.

Something to ponder when the next “clean girl” make-up trend pops onto your social media feed…

PS: *I want to emphasise that there absolutely nothing wrong with choosing to be a housewife or embracing homemaking (I’d probably be the one in most of my friendship groups who enjoys homey things the most.) The issue lies in how it’s become a rightwing aesthetic and how it so often presents submission, domestic labour, and female self-effacement as aspirational, glossing over the historical inequalities that made those roles compulsory rather than chosen. Wrapped in nostalgic pastel filters or even the more modern guise of “natural or clean beauty” it can mask a regressive worldview that conflates femininity with servitude, and aligns itself with the darkest systems of oppression in our society.

-Buy ‘UGLY: Why the word became beauty obsessed and how to break free’ in the UK here, in the US here and click here to for other countries.

-Follow me on Instagram here

-Find out more about my work here.

I think you nailed it. I never really thought of it that way, but you're right. And being a housewife or stay at home mom can be rewarding, but it's also stressful and difficult. Women judge each other so harshly about it, and yet it's something all mothers face, whether they need to or choose to work outside the home. (I have done both so I do not judge at all).

It's interesting how fashion trends correlate to this as well, now that I'm thinking about it. The lace, the dainty accessories, the conservative cut of fabric.

Huh. Thank you for this fascinating read.

I knew social conservatism was coming back when the kardashian’s started dating white guys again