"The use of arsenic in beauty products made absolute sense in the context of the time...

Historian and beauty lover Lucy Jane Santos gives us her fascinating take on beauty trends of the past...

The history of beauty culture offers us many useful things.

It gives us insight into practices that make us gasp with their outlandishness - hello medieval hairline plucking - but it also gives us the context behind things we think are ‘fact’, like blonde hair and blue being seen for so long as the most desirable attributes (hai Eurocentric beauty values) and crucially, it’s a way to gain insight into the lived experiences of people of the time.

I’ve been a fan of historian

and her brilliant Substack, Past To Present for a while, so I’m very excited to share this interview with her. Prepare yourself for a fascinating journey through beauty history and her incredible mind …ANITA: Hi Lucy! How do you describe what you do? I’ve seen you on documentaries and know you’re an author too?

LUCY: I’m an independent historian which basically means a freelancer – so I find work where I can and do a wide variety of projects and tasks including presenting, writing, proof reading, fact checking as well as the occasional consulting for TV and films. And yes, I am also an author and have written two non fiction books history of science books about radioactive elements. I’m also a huge beauty fan - so that crosses over into my work because of personal interest.

A: Ah fascinating. So what piqued your interest in beauty?

L: I was really into the vintage scene around 2010/2011, and had started doing a fun sideline with some friends where we helped people with their make-up – getting the perfect eyeliner flick and pout – but we wanted to add value to the experience, so I started talking about the history of cosmetics. I always joke that the people who came to our workshops just wanted to have fun, drink a cocktail and learn some skills – but I always ruined the vibe by droning on about the effects of rationing or the politics of appearance. But I do think people enjoyed it really.

It was also around about that time that I became absolutely fascinated with the science and technology behind cosmetics and beauty practices – the ingredients, the people who made the products and especially the reason why people bought and used products that were known to be dangerous so lead, mercury, arsenic and radium in particular. That question was the reason I began the research that eventually became my first book Half Lives: The Unlikely History of Radium.

A: What's the oddest beauty trend/device/practice you’ve come across?

L: Because we are talking about practices that have been in existence since the beginning of time (people have always wanted to modify their appearance in some ways) there are so many examples of things that seem odd. Some, of course, can be due to cultural differences and it is so important to be mindful of why people used things that maybe don’t make sense to us. There is often this idea that beauty practices are rooted in ignorance and vanity – largely because we are often talking about the way women changed their appearance – and that means beauty history is often not taken seriously.

But saying all that I am absolutely obsessed with dimple makers, nose shapers and lip formers – all devices that claim they can change the shape of parts of your face or give you dimples. They have a long history and are remarkably resilient in the sense that they keep getting made and I have examples from the 1900s that look pretty much the same as the ones you can buy on eBay today – other than the early ones are metal and todays are plastic. I also absolutely love the Mark Eden Bust Developer (above) a little clamshell device made from plastic with a spring in the middle that you squeeze, and they claimed it would give you the perfect bust.

A: Oh wow, that’s quite something! I’d love to know what shocked you about the way that beauty culture and history intertwine?

L: I’m not sure if it shocked me, maybe it should have, but it is really the ways in which such an important practice has been minimised as ‘girls’ stuff’ and not given the historical consideration it should have been. Beauty culture at its widest encompasses everything we do from getting up in the morning and washing our face, protecting it against the sun, cleaning our teeth to getting ready for bed and everything in between.

Beauty culture is not just about choosing the right shade of pink lipstick, but it is about controlling the face and body we present to the world. And at the same time, it is also about the way the world controls people whether that is diminishing individuals or justifying the ill treatment people based on their skin colour, gender or whatever characteristic is deemed undesirable at that point in history.

A: I loved something you said in your conversation with make-up artist Erin Parsons on her documentary about how Queen Elizabeth I (above) was often pictured inaccurately, likely due to anti-women sentiment at the time. Could you explain more about that?

L: Yes, that was a particular reference to the way that male authors and artists in the Victorian period talked and represented her. She was consistently described as being covered in thick make up and grotesque – especially as she aged. It is these descriptions that have influenced how we all now think of the Queen today and how she is often depicted in movies – a vain, haggard women desperately trying to conceal her flaws.

The trouble is – it kind of wasn’t true. Yes, she aged, yes she probably did do things to appear younger, but the visceral delight in describing a woman aging is more about those Victorian writers. This is a time when women were gaining more power, more freedom and it upset many people’s sense of what was the natural order of things. Striking at women from the past who had power – to show that this was not normal, not natural – was a way of proving that it wasn’t right for women to be in control. It’s almost a warning – look at what might become of you.

And really the problem with most of our sources about beauty practices from the past is that a lot of evidence we have is from men – whether that is artists depicting beautiful women or writers describing them – so that misogynistic lens is really not hard to find. To get a real sense of what women thought was beautiful, what they wanted to achieve its important to look beyond those – a good resource is the household books written by women which list recipes for cosmetics, to letters written sent between friends sharing tips for example. I know you interviewed Jill Burke recently and her book is absolutely wonderful for giving a sense of the community that can be built around beauty practices and the joy and satisfaction that can come with it.

A: Are there any beauty myths in history that we think are true, but are actually false?

L: Well one of the most fascinating ones is the work that Erin Parson’s has been doing on lead makeup and whether it really was a thick white paste or something much more subtle. It has been fascinating to be part of the team of historians, cosmetic chemists as well as Alicia Schult, who runs an apothecary. Alicia’s research at LBCC Historical Apothecary is absolutely crucial for investigating our assumptions about past beauty products because she goes back to the original recipes and recreates them. She has taught me so much about not only ingredients but how these products have been made and the science behind them. Is absolutely fascinating.

It is through people like Alicia, Erin and other researchers – and at this point I should mention the Cosmetic History and Makeup Studies Network who are a group of beauty historians – that we are reevaluating our understanding of past beauty practices and the myths that have come down to us. And being interdisciplinary we can unpick the roots of myths and what they can tell us in themselves.

A: What beauty invention do you find most fascinating historically?

L: Its actually a series of inventions that I find the most interesting – and more specifically the invention of technologies that allowed people to see themselves in particular mirror and then photographs.

We live in a world where seeing ourselves is part of daily life – we carry that technology in our pockets. But to live in a world you could only see yourself as a reflection in water or on smooth metal and then the change as good glass mirrors gradually became available and what that meant to your ideal of self is fascinating.

And then again when photographs meant that people could see themselves captured in a period of time – years after the fact. And films which captured not only likeness but movement as well.I know that these are not specifically beauty inventions but would have had such an effect on how people thought of themselves.

A: Why do you think beauty/danger has such a high crossover historically?

L: Anything to do with body intervention – whether that is surgery or even binding your feet – is by its very nature risky especially in times when access to healthcare was limited. At the same time emerging technologies are also not fully understood – just because you can do something doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. A really good example of this is X-ray technologies – the rays were discovered in the late 1890s and almost immediately came to be used in a hospital context as it was realised that they could be used to burn away skin diseases and even tumours. At the same time hair loss was observed to be a side effect and so very soon they started to be used in salons as a hair removal treatment. They truly were a modern marvel offering a much better experience than the other hair removal techniques around at the time so became very popular. It was known that in inexperienced hands X-rays could cause severe burning of the skin but what wasn’t truly understood – was that years down the line many of these women would develop tumours from their use.

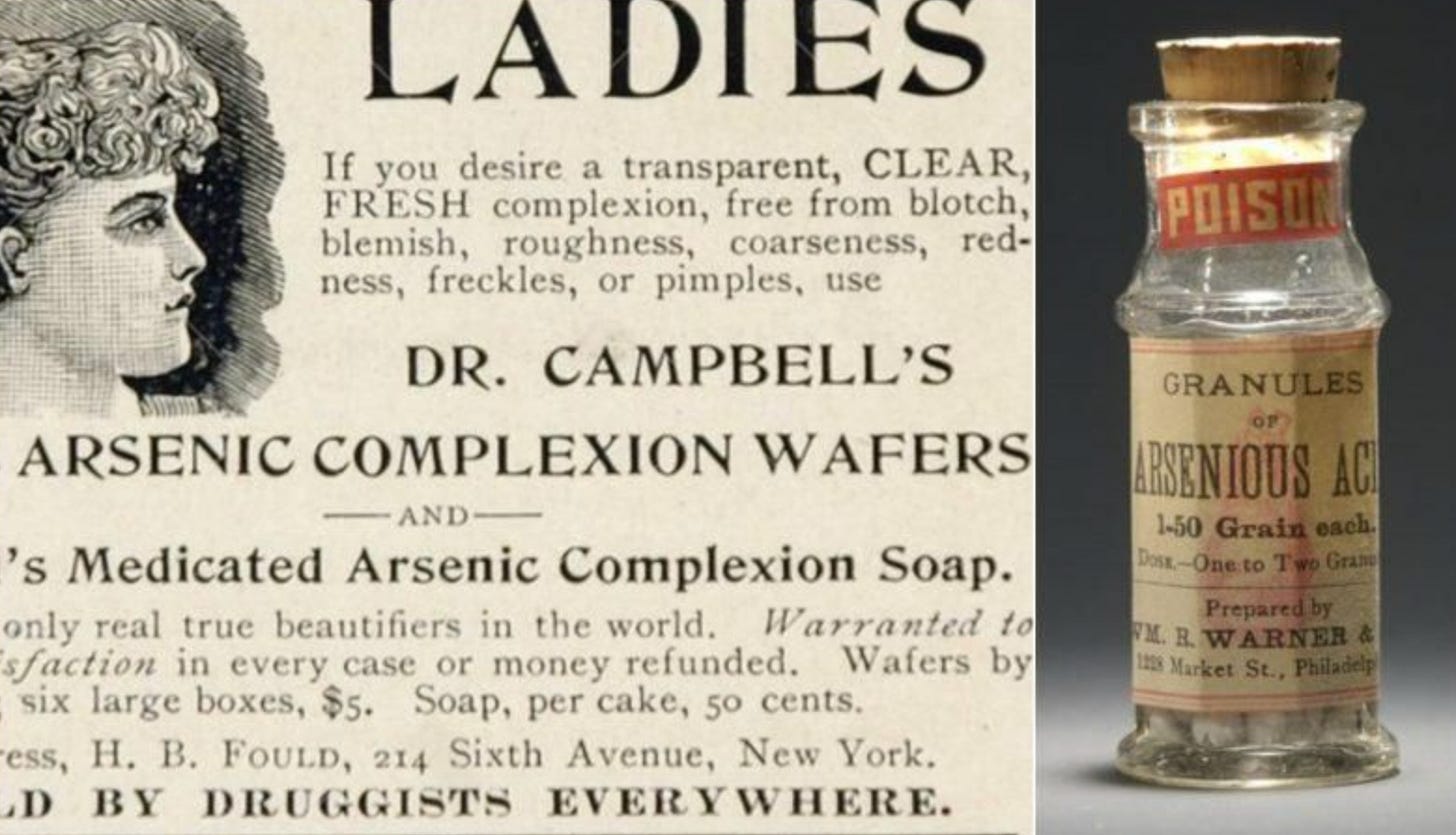

And what is really interesting is the intersection between beauty products and practices and medicine in general. A good example is arsenic. There are often articles on the internet called something like ‘Shocking Beauty Products Used by Our Ancestors’ with the subtext ‘what on earth were those stupid women thinking’ that show an example of Dr Campbell’s Arsenic Beauty Wafers (above) or one of the other numerous products that were available at the time.

We read them and are generally glad that we have safer and more effective products at our disposal. But actually, the use of arsenic in beauty products made absolute sense in the context of the time. It was an ingredient that was touted by the medical professional at the time as almost a panacea – something that could cure all ills. And it does seem to have been quite effective – small amounts of arsenic give your skin a natural flush (its to do with capillaries in the face dilating), it can clear up spots and has various other benefits. Now of course taking too much of it or taking it for too long is absolutely dangerous but as a short-term solution the risks were largely outweighed by the benefits.

So there are lots of reasons why something used in the past can seem dangerous to us now – either through the benefit of hindsight or through a loss of context – but it absolutely made sense at the time.

A: I did read that there were radioactive elements in beauty products for while, how did that come about?

L: I mentioned emerging technologies earlier and the use of radioactive elements in beauty products has a similar trajectory. Radium, which was discovered by Marie Sklodowska Curie in 1898 also emitted invisible rays that, like X-rays, burnt the skin. So, it became used in hospitals and for a while it really seemed that cancer was going to be cured. People got really excited and soon found all sorts of ways in which it could improve people’s lives and health. It wasn’t just that it burnt off tumours and skin diseases but that the element decayed it turned into radon, which is a gas. Radon also seemed to offer health benefits, in the form of something known as Mild Radium Therapy and was also hailed as a wonder treatment for curing everything from bronchitis to rheumatism.

The beauty industry soon began adding radioactive elements into their products. So you get tiny amounts of radium salts being added to face powders or radium infused solutions being marketed as hair restorers. And, just like arsenic, radium does seem to have genuinely worked to an extent at least!

Small amounts of toxic ingredients do stimulate the metabolism – they give your face a flush, improve the skin, make you feel invigorated. And we all know the experience of buying a new product – especially one that has been heavily advertised or has a celebrity endorser exclaiming its virtues – and the joy when it actually does seem to live up to the hype. Your skin feels fresher, the wrinkles a little reduced – maybe you have finally found that product that is going to change everything. Mostly a few months down the line you are a little less impressed and move onto something else of course.

And I think that is something that is worth mentioning with the use of beauty products- I often get asked about whether there are lots of women dying because of their use of radium products and the answer is no – the evidence is just not there. Its largely because of the minute quantities that were used (and sometimes the products were fraudulent in any case) but also because often just like today a wonder ingredient is announced, companies leap on it, we buy it, use it for a bit and then just move onto the next. On the whole people are not building up massive amounts of toxic ingredients in their systems just from using beauty products.

A: Can you tell me about your new book? What inspired it?

L: My new book is actually a prequel/sequel to my first one because I wanted to tell the story of where radium itself came from. So, I trace the history of uranium (which decays into radium, then radon and eventually lead) and all the different ways it has been used from medical treatments, to colouring in glass, to bombs and nuclear energy. I also look at the cultural connotations of it which include an absolutely fascinating period of American history where the government incentivised individuals to go uranium hunting in the desert – and the industries that sprung up because of it. So you get shops selling Geiger counters, magazine spreads showing the latest in uranium hunting fashions as well as a plethora of songs and films. At the same time atomic bombs are being tested in the desert outside of Las Vegas and the whole town becomes obsessed – there are bomb watching parties, cocktails, hairstyles and even an atomic singer – Elvis Presley.

A: I’d love to know if you have a favourite beauty product?

L: It has to be Chanel No 5. I love the history of how it came to be, the science behind the scent, the way it has been marketed in the past and its status as a heritage brand today. On a personal level it was the perfume I wore when I was a teenager (I was Marilyn Monroe obsessed) and the smell instantly takes me back to that point in my life. It often surprises people that for someone who talks about beauty so much I am actually not that clued up about makeup and wear comparatively little myself. Maybe am just waiting for someone to reissue radium lipstick and mascara before I commit fully!

A: Finally - I’d love to know the beauty icon you find most fascinating in history?

L: I am still fascinated with Marilyn Monroe – not just because of the way she looked and her acting chops but the ways in which her image has been manipulated and shaped. This is someone who fitted into the dominant ideals of the time but was still in many ways punished for it. It is someone who decades after her death is still used as a shorthand for a certain type of beauty even as her legacy is distorted, her flaws magnified and her talents diminished. And now we even have ‘Digital Marilyn’ (above) a truly depressing interactive representation of her created with AI.

A huge thanks to Lucy for all her incredible insights - find out more about her work below too!

Much love (and no arsenic)

Get more Lucy below:

-Check out: Half Lives: The Unlikely History of Radium

-Pre Order: Chain Reactions: The Hopeful History of Uranium (released July in the UK and September in the US.)

- Join Lucy on Substack here

- Find out more about Lucy from her website here

- Follow Lucy on Insta here

What a fascinating read! I recall my first encounter with this “beauty culture” to be in “Little Women”, when Amy tries to pinch her nose to make it pointier. I was utterly confused to say the least!

I’d argue one thing though- the blonde blue eyes combination is not much “European”, is more white-Anglo-Saxon. A huge chunk of Europe is located around the Mediterranean or Black Sea and these characteristics are also “alien” to most of us -not yet dark enough to be “brown people”, but definitely not WASP :)

Incredible read as usual. Thanks for sharing. 🫶🏻🥰