Why did acne become a source of shame?

Surprisingly, a trip New Orleans reveals some of the answers....

TW: Just FYI, I mention historical accounts of slavery in this column that may be upsetting.

I spent Christmas in New Orleans, quite randomly. I haven’t been in 15 years, and the city has changed a lot since then. There’s something quite magical about it; a combination of the live music culture, history and diversity too. I fell in love with it again and might even go back this year. I also managed to book my family into a World War II themed hotel TOTALLY by accident (why does nobody - including my family - believe me?!)

On my travels I visited the Laura Plantation which dates back to the 1800s and is now a museum and cultural centre. The history of it is based on the memoirs of its last owner Laura Locoul Gore (1861-1963) who wanted to preserve it’s stories.

Many of these stories are tragic and deeply upsetting as you’d imagine for a plantation house that has its roots in slavery and colonisation. But there was one story I found fascinating from a beauty perspective, because it shows how enduring the ‘power of pretty’ is and lead me to investigate the history of acne. So sit back, get a cuppa and let me regale you with it…

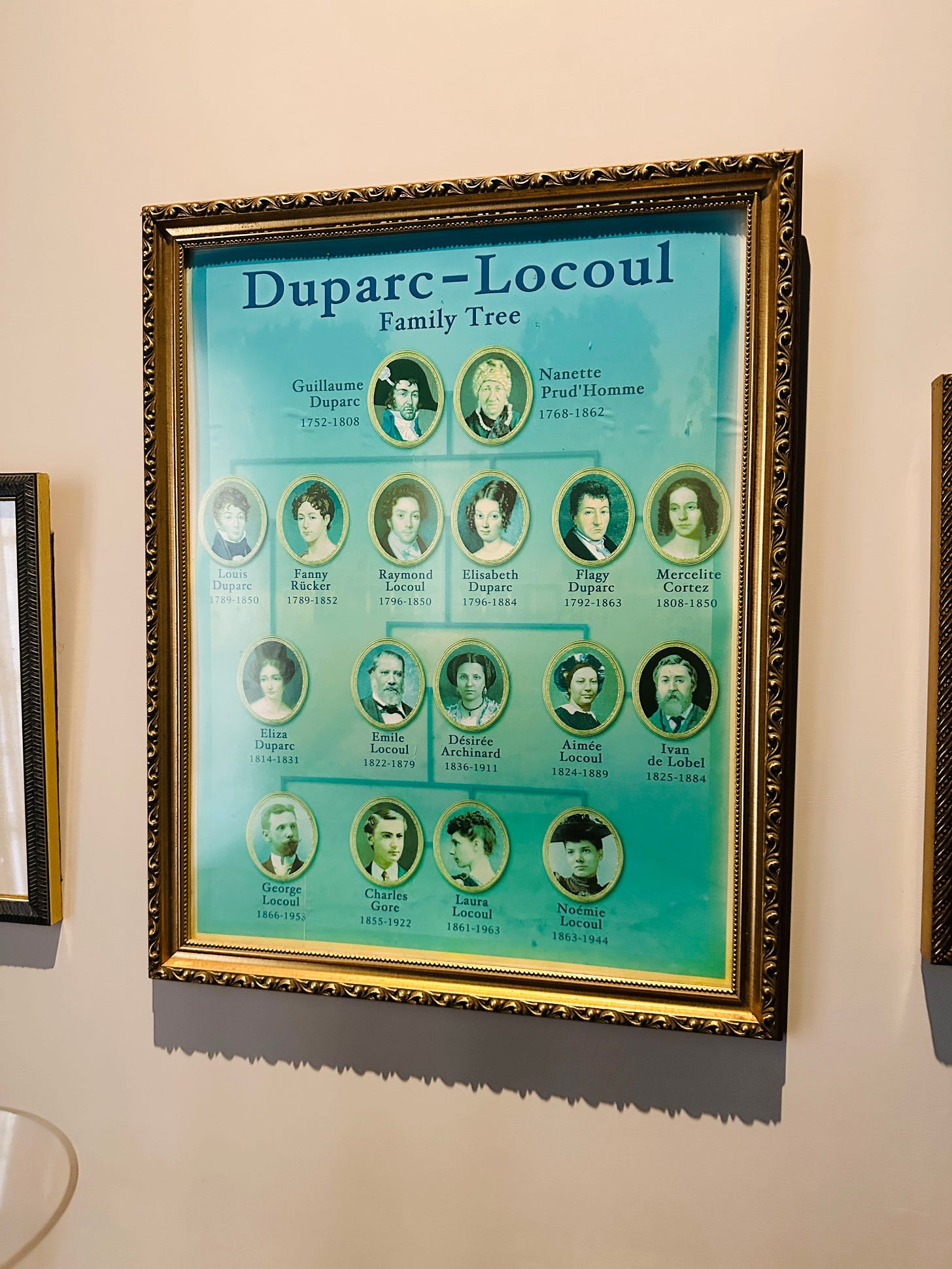

In 1804 General Guillaume Duparc arrived in New Orleans after fleeing from France after essentially murdering someone, which isn’t a great start tbh. He then decided to build a manor house right in the middle of a Colapissa India village that had been there for over a century. He does make a lot of dick moves, but when he dies in 1808, his wife Nanette becomes the first female president of the plantation. That’s one cool thing to note; some women were allowed to have these roles back then in Louisiana. But sadly, Nanette - like her horrible husband, was not ideal. She separated enslaved mothers from their children and practised the awful branding of slaves.

Nanette’s daughter Elisabeth (who is very much the favourite) took over the running of the plantation in 1830 - much to the chagrin of her elder brother Louis who was generally an angry and unpleasant sort of chap. At one point he gets so angry when she inherits the plantation that he even kills two slaves in a furious rage. Was he imprisoned or reprimanded? Was he f*ck. All he had to do was to pay the owners of the slaves, meaning he literally got away with murder. To get him out of the way whilst all this was going on, he’s given some money and sent to France where Louis marries Fannie and they have a daughter Eliza. They end up returning to Louisiana when Nanette threatens to cut him off financially, and becomes the plantations business manager. Nanette then dies during the American Civil War aged 94, when a bomb hits her retirement home on the estate.

In the midst of all of this chaos, Louis’s brother Flagy also ends up managing the plantation at one point and has children with several of the female slaves (above). This wasn’t uncommon back then, but what’s really sad is that many of these children were likely born from rape and coercion. He denied his children, obviously.

So back to Eliza - Louis and Fannie’s kid. Eliza is the favourite, until she becomes a teenager that is. Thats when she develops acne, which sends her parents into a frenzy because their beloved daughter is now ‘ugly.’ They most likely fear that she won’t be able to secure a good financial marriage match, so to cure her acne, they visit France to seek a ‘miracle treatment’. What does this miracle cure involve, pray tell? You guessed it, something hideous. The 19th century cure for beauty ills was often something grim and poisonous - and she was given an arsenic based cure. Sadly, the doctor administering the acne cure got the dose wrong, and Eliza dies - in vain.

Fannie is distraught - as she should be. She and Louis essentially prized Eliza’s beauty - and what it could bring the family - over her life. Fannie is regretful, at least: she says: “I no longer expect anything pleasant in my life. That has been my destiny, always sorrows and anxiety. That is how I spend my life and I am utterly annihilated. I am sure that I will never be happy, ever again.” Louis however, can't cope with his wife’s melancholy, so he ditches her and takes two teenage slaves as concubines instead. SIGH.

I’m stopping on the family history here, but there is a whole legacy after this point, so if you’re in New Orleans or Louisiana then definitely visit the plantation (and the many plantations of the area). We have a duty to remember these things, I feel.

During the tour, I did find the tale about Eliza fascinating. There have been mentions of acne throughout history that it seems commonplace, which made me wonder why this was such a big deal to her parents, and how did it speak to the beauty standards of the 19th century?….

Back in ye olde times, the cause of acne thought to be an internal imbalance of humours according to Ancient Greek physicians like Aristotle and Hippocrates, whilst the ancient Egyptians called it aku-t. At various points in history, it was also linked to being fertile, chaste and masturbating too much (LOL) but it doesn’t seem to be feared as such - and not to the point where you’d risk so much for a cure.

There does seem to be an increase in the stigmatisation around acne and skin issues during the 17th century, which a report by British dermatologists attributes to Shakespeare. He does seem to be obsessed with skin to be fair; King Lear tells his daughter: “Thou art a boil, A plague sore, an embossed carbuncle…” and in Henry V, Bardolph is described by Fluellen: “His face is all bubukles, and whelks, and knobs, and flames ‘o fire…” Phrases like ‘a pox upon him’ were seen as deeply insulting likely because of the prevalence of disease in Elizabethan England. But Shakespeare’s influential writings and his depictions of skin probably did add to the stigma round acne.

What else added to the stigma? The British class system. Early thoughts on dermatological issues suggested that acne was a working class problem (which might also explain why Fannie and Louis were freaking out about it.) Since the 17th century the contagion theory - which said that disease could be spread by touch, food, clothes or people - had suggested that even being near poor people meant you’d catch their skin issues, which sadly ended up justifying abuse of the poor and destitute. The rising middle classes were also keen to be seen as cleaner, and wanted to pull away from the lower classes to distinguish themselves. And if you were wealthy or had a bit of money, you would have had more access to clean amenities, food and rudimentary medical care (like balancing humours and er, prayers.) The beauty standard of the time was pale, unblemished skin, which denoted class and good breeding - and Eurocentric beauty standards too.

In 1840 the term ‘acne vulgaris’ was coined (vulgaris meaning common) and English physician Samuel Plumbe wrote about acne being caused by blockage of the sebaceous glands. English physicians Robert Willan and Thomas Bateman also divided acne lesions into four different groups which also included rosacea. Dermatology was becoming important and more sophisticated, but it seemed like treatments lagged behind, often consisting of botanical remedies and curious dietary changes.

If you’d had some herbs and were told to cut out meat, you’d be laughing compared for what was in store for acute acne patients. In the 19th century, calomel pills (see above) were used to treat acne. These pills were part mercury, part sugary substance and it was tough to know exactly how much was actually being administered to patients - let alone cope with the awful side effects like mercury poisoning, gangrene of the mouth, cramps, vomiting (and death.) They generally thought these conditions were due to the body purging itself, rather than as the result of the calomel pills themselves, until later in the century when the penny finally dropped.

Arsenic, however, was already known to be poisonous, but despite this it was used in many beauty cures, including acne. That’s important to note when we look at our modern beauty culture; often we know there’s a downside or a serious risk, but we do it anyway. Beauty is still so valuable as a personal commodity that it’s worth risking our lives for by undergoing risky cosmetic surgeries or backstreet procedures. And back in the 19th century, Fannie and Louis were willing to risk anything to make Eliza beautiful again. Even death, it seems.

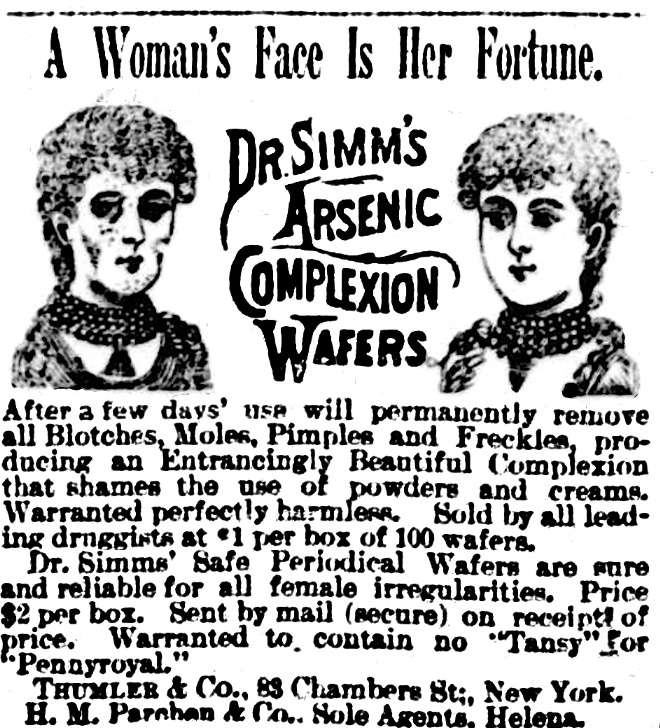

These cures were seen everywhere. US newspapers advertised products that promised to give a clear complexion called Arsenic Complexion Wafers. Did the media companies profiting from the ad money care about the risks? Nope. Did the company or doctors making those products care? Hell no. Were these products largely aimed at women? You bet. It just shows how much these industries did - and still do - care more about their profits than they do about our safety.

Acne has had years of being chastised, feared and shamed. But not because there is anything abnormal or shameful about it, it’s because of the ways it’s been linked to class, Eurocentric beauty values and the outdated premium put on female beauty, throughout history. That’s just a little something to remember if you’re struggling with it, and hope you found this as fascinating as I did.

Much love…

Thank you for this, have had to manage chronic persistent acne for years. This is so interesting!

Fascinating history and writing as usual. Thanks for sharing!